What makes a teacher?

Several years ago a librarian colleague said, “I teach, but I don’t teach, you know?” in a conversation about using peer observation to reflect and improve upon our teaching. At the time, this statement did not make any sense to me. Even considering there might have been a little bit of defensiveness in response to the idea of peer observation, that statement confused me at face value. How can you teach but not teach?

It’s been years and I think I finally found the answer. Or at least a perspective on how some librarians feel about their identities as teachers. A couple of weeks ago, my summer reading group read the article “Am I a Teacher because I Teach?” In the literature review, Kirker cites a study of British librarians and how they viewed their roles as teachers. That study categorized the four identities as:

- “teacher-librarians” (teachers who teach)

- “learning support” (teachers who do not teach)

- “librarians who teach” (non-teachers who teach) or

- “trainers” (nonteachers who do not teach)

When I read this, I thought of my former colleague. Although I was a newish librarian at the time, I was very confident in my teacher-librarian identity. This was based on my coursework in graduate school, the enormous number of one-shots I did as an adjunct librarian at a community college, and the role I eventually held at that institution alongside my colleague. I have a new role where I actually don’t teach many one-shots and I still consider myself a teacher-librarian. Even though my former colleague had been in the profession much longer than I, they still did not identify as a teacher. They likely would use any of the categorizations above except for “teacher-librarian.”

One of the participant’s in Kirker’s study discusses how librarians are not teachers because students are not accountable to us in the same way as their professors. We do not give out grades, we don’t require excused absences, we do not develop the same connections with students as their semester-long professors, and, in the end, we are not experts in subject content. Besides the relationship-building aspect, much of this is true. But I don’t think this is how we should define our teaching identity.

I think the final section of Kirker’s article can help us consider our identity: “student learning is the core of teaching in the academy.” We may need more professional development and training in pedagogy or more support from our academic colleagues, like course instructors. However, if we are invested in student learning then we can consider ourselves teachers.

I’m interested in hearing from you about this topic. Do you consider yourself a teacher?

Pause with a Poem: A Break for Well-being

On May 11, 2022, Penn State kicked off a university-wide health and well-being program headed by benefits strategist, Rita Foley, with a mission to cultivate “a thriving workforce that is engaged in health and well-being and is a role model for the communities in which we live and work.”

One of the program’s initial steps – taken up by well-being ambassadors across university locations, colleges, and departments – was to invite colleagues to the wellness webinar “Depression, Anxiety, Burnout: Moving Toward Hope and Health,” presented by Health Advocate Employee Assistance Program manager, Karen Rech, on May 20.

One definition of burnout Rech provided was: “a state of emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion caused by excessive and prolonged stress [that occurs] when you feel overwhelmed, emotionally drained, and unable to meet constant demands.”

To prevent burnout, Rech presented tips that included (among others):

- Consider alternative mindsets.

- Relax your body.

- Calm your mind.

- Take 10-15 minutes to reflect.

Researchers and sisters, Emily Nagoski, PhD, and Amelia Nagoski, DMA, write in their book Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle (Ballantine Books, 2019) that “the ultimate moral of the story” is:

Wellness is not a state of being but a state of action.

— Emily Nagoski and Amelia Nagoski

Amid churning out work at your computer, pausing with a poem can satisfy all four actions above to stave off burnout, and the Pennsylvania Center for the Book (PACFTB) at Penn State University Libraries provides a ready resource with digital content from its poetry initiatives.

The PACFTB, an affiliate of the Center for the Book at the Library of Congress and sponsored by Penn State University Libraries, supports its mission to encourage Pennsylvanians to study, honor, celebrate, and promote books, reading, libraries, and literacy with multiple initiatives, including the Public Poetry Project, a project that features work by Pennsylvania poets on print/digital posters to be distributed freely, and Poems from Life with Juniper Village, a collaboration with Juniper Village Senior Living at Brookline that celebrates its residents with original, individualized poems generated and presented by local poets.

A poem intentionally leads readers into an alternative mindset, a state Rech recommends pursuing as a first step to avoiding burnout.

“Somewhere, a child pretends to sleep—,” begins “Vow” by Erin Murphy, selected for the Public Poetry Project in 2020. What follows is a cadence of “fluttering” imagery with potential to both relax the body and calm the mind, checking off the next two tips for deflecting burnout.

“Poetry can provide comfort and boost mood during periods of stress, trauma and grief,” science writer Richard J. Sima, PhD, states in his overview of recent studies, “More Than Words: Why Poetry is Good for Our Health,” for The International Arts + Mind Lab at Johns Hopkins University. “Its powerful combination of words, metaphor and meter help us better express ourselves and make sense of the world and our place in it.”

If several readthroughs of the poem only occupy part of the forth recommendation of 10-15 minutes of reflection, a video of Murphy reading “Vow” is available on the PACFTB’s YouTube channel, which houses a variety of craft talks and presentations that document awards and programs.

“The River Bathers” by Elaine Terranova, from the 2003 Public Poetry Project, is another piece that pauses the busy mind and “[takes] in breath enough / to get me through” with kinetic language that sooths and transports readers into a current of mythology and the resiliency of nature.

Carolyne Meehan’s “Wedding Photo” reads, “…her bobby pin … how she must have / rolled and then slipped / pin after pin, / row upon row,” and likewise carries readers with sensory-rich momentum through a scene dedicated to and informed by her shared conversation with Juniper resident Harriet O’Brien as part of the 2020 Poems from Life program. A video of Meehan reading “Wedding Photo” is also available.

In Psychology Today, Deborah Serani, PsyD, cites the positive outcomes of reading poetry and other forms of literature in her article “Bibliotherapy for Depression,” and these include, but are not limited to: “reduction of negative emotions, deepening insight, increased empathy and compassion, [and] greater social connection.”

Buzzing with the flow of community and “the rhythmic sound / of straight razor on leather strop…,” Sarah Russell’s “Fred Harris, American Small Town Barber,” reflects on the life of a Poems from Life 2017 Juniper resident and provides alternative perspectives on the values of staying rooted verses traveling the map.

The added hint of a warm audience captured in the video of Russell reading her poem encourages sharing in community and conjures the power of “collective care,” a term discussed in a presentation and conversation with Dr. Abigail (Abby) Phillips on May 16 during this year’s Staff Diversity Week at Penn State University Libraries, organized by Maggie Mahoney, James McCready, Alex Harrington, and Jackie Dillon-Fast.

Collective care was discussed as “part of self-care with a connection to community” and reminds us to reach out to neighbors, loved ones, and resources in those times when we need more than a poem.

For more information about PACFTB poetry initiatives and other literary programming, awards, and resources, please visit the PACFTB website.

I have been thinking a lot about how information consumption and information literacy (IL) are part of a larger identity development process. This line of inquiry pulls together information literacy instruction, cultural norming, and psychology. While this question applies to all users, because I am an instruction librarian at a state university, I have been thinking about it as work with college students. College can be a transformative moment where students learn about worlds outside of their own, consider new ideas, and meet people outside of their normal circle. College students are in a pivotal developmental stage of life, where they are experiencing autonomy and experimenting with their adult identity. As JJ Arnett (2000, 2014) highlighted, this stage of human development is extremely focused on identity development and exploration. This reframes how I think about IL for my students—it can frame how they evaluate new information before it assimilates into their prior knowledge, how they define expertise, and how they evolve from a novice to an expert in their field.

When ALA and ACRL proposed a threshold model for information literacy, it positioned information literacy as a cognitive process with dispositions – or “valuing dimension of learning”— and practices—the behavioral “demonstrations” of learning (8). As information consumers develop IL skills, the way learning shapes their values and affects, which in turn shapes their identity. As a framework of threshold concepts, IL shifts a concrete checklist of actions to a process to integrate new information that impacts identity.

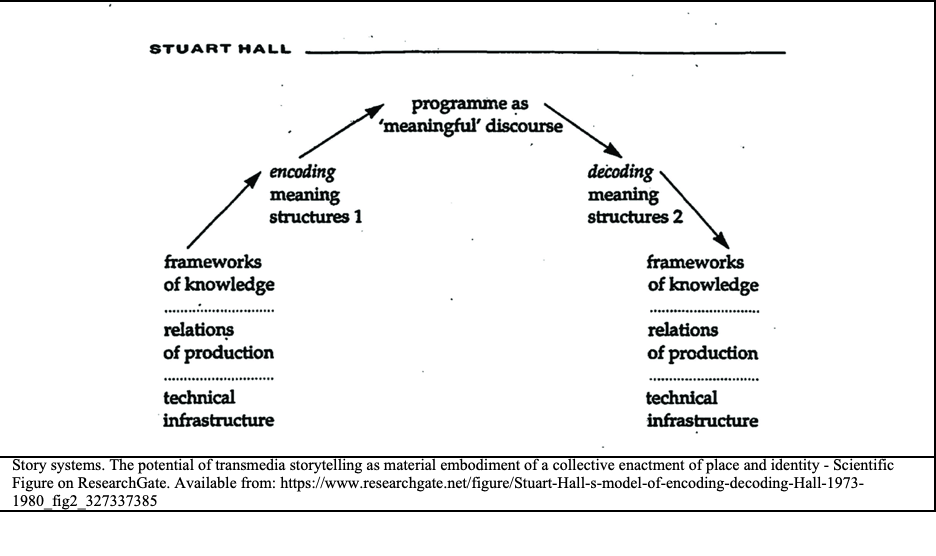

This is where my cultural studies interest comes into play. The basic premise of cultural studies is that as individuals create cultural artifacts (information) they put their own meaning into it (encoding). That information is assimilated into this larger information ecosystem that is all connected then other individuals consume those artifacts that are full of diverse information and assimilate it into their own vales and meaning making (decoding). This cultural process can clearly be framed within IL— how individuals relate to information, how they evaluate information, and how they create new information incorporating prior knowledge and connected information.

The cultural and cognitive components of IL have led me to another key question- how information consumption and creation impacts the individual and their identity. I found some interesting ideas in Psychology: self-concept and fusion. Self-concept is “broadly defined as a person’s perceptions of himself or herself” through fusion which outlines how an individual processes their identity development by integrating “constructs,” or information, into their self-concept (Williams 2017vii). Constructs can be: “a person’s thoughts … beliefs … opinions …arguments … … and values,” all of which are direct outcomes of information literacy process (3). Interestingly, like information literacy and research, fusion is an iterative journey to self-concept- “the more one perceives a construct as fused, the more the construct is included within the knowledge structures of the self” (Hatvany et al. 2017). The more an individual evaluates and uses ideas and information that agree as they follow different lines of inquiry, the more they connect with the associated concepts and shape their identity.

As I have read more about information consumption, cultural constructions of identity, and fusion with constructs to shape self-concept, I see clearly that all of these processes lead back to how people learn to find, evaluate, organize, use, and communicate information on a regular basis. Now, when I teach I am aware that the ways I model evaluation, the ways my students develop and research their topics, and the information literacy skills they learn all shape how they see themselves and construct their identity. I am still wrestling with the relationship between these ideas, and how it informs my teaching practice, but they offer an interesting perspective on the stakes of information literacy and its impact on our students.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Arnett, J. J. (2014). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. Oxford University Press.

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2016). Framework for information literacy for higher education. Retrieved from https://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/issues/infolit/framework1.pdf

Hatvany, T, Burkley, E, Curtis, J. Becoming part of me: Examining when objects, thoughts, goals, and people become fused with the self-concept. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2018; 12:e12369. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12369

Williams, M. (2017). Self-concept: Perceptions, cultural influences, and gender differences. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Notes About Note-Taking

A few months ago, a colleague wrote about creating an online tutorial for Zotero instruction. After reading April’s post, I thought about my own experiences with citation management tools.

I was familiar with the citation managers used by faculty and students, but didn’t consistently use one myself until a year ago. Then, early in a group writing project, Zotero was suggested as a way to share literature and annotations.

This reintroduction came just in time to keep me on track for overlapping publication and presentation deadlines. Finding my notes on important points and their sources was much easier than sifting through file folders of stapled printouts (or an unwieldy stack of papers, not that any of us have experience with that).

Looking back, I think using a citation manager to organize my articles and thoughts helped me multitask a little more effectively. Zotero 6, the latest version, incorporates PDF features like exporting and storing annotations, as do other citation managers.

Tools like Zotero can be useful in other circumstances, too. For example, I’m participating in three reading circles/discussion groups this summer. I’m able to attend at least two meetings for each group, and didn’t want to lose track of what was next. Rather than printing everything, I created a Zotero folder for each group that includes the assigned PDFs and my notes. Before each group’s (virtual) meeting, I can quickly access my highlights for that session’s reading and refer to them during the discussion. I haven’t noticed a difference in what I’m retaining, and I’ve saved paper and office clutter.

Reading and annotating on a screen isn’t for everyone, of course. But if you’re thinking about giving your highlighter a break, choices range from mobile-friendly note-taking apps to research-focused platforms. Asking colleagues about their experiences and considering what’s used most at your institution can lead you to a few options to explore. If you’ve found an application that’s been a good fit for your citation and note management, please share it in the comments.

The important thing is finding (or continuing) a system that works for you — including tried-and-true post-its and paper stacks.

Presented by Steven Bell

July 14, 2022 at 11:30 am EST

This presentation introduces attendees to the Five Revolutions of Higher Education. It is less about predictions than surfacing societal trends that are already impacting and will continue to reshape how and to whom higher education is delivered. The five revolutions are:

* Demographic Revolution

* Socio-Cultural Revolution

* Economic Revolution

* Technological Revolution

* Learning Revolution

In 2020 we experienced a new and sixth revolution – the global COVID pandemic. We will reflect on how these revolutions are altering the higher education landscape, but more importantly, how, in 2022 and beyond they will support or detract from the efforts of academic librarians to create cultures of openness at their institutions.

Whether it is leading the way for open access journal publishing, supporting instructors to flip their courses to open educational resources or adopting open pedagogical methods, the open movement in higher education is a critical component of academic librarianship’s mission and significant contributor to its sustainability. Using these revolutions as a perceptive lens, Steven will encourage attendees to engage with academic openness and support its advancement in higher education.

Steven J. Bell, Ed.D., is the associate university librarian for research and instructional services at Temple University. He writes and speaks about academic librarianship and higher education, change readiness, educational technology, open education, design thinking and user experience. He currently teaches design thinking and open education courses to MLIS students at the San Jose State University iSchool. He authored two columns for Library Journal, “From the Bell Tower” and “Leading From the Library” from 2009 to 2019, and currently contributes a monthly blog post on academic library topics to the Charleston Hub. For additional information about Steven or links to his projects, visit his info page.

As a reminder, the Zoom link will be sent approximately 48 hours before the session. We will mute participants on entry into the Zoom room. Session will be recorded and available on YouTube after the session. We will enable Zoom’s Live Transcription feature during the session.

If you would like to present with C&CS, please contact the C&CS team.

This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries, and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Tom Wolf, Governor.

Support is also provided by the College and Research Division of the Pennsylvania Library Association.