October Virtual Journal Club

The first meeting of the Fall 2022 series of the Virtual Journal Club, sponsored by the College & Research Division of the Pennsylvania Library Association, will be Thursday, October 20th, 2:00-3:00. This series will focus on libraries and literacy. We will discuss:

Donovan, J. M. (2020). Keep the books on the shelves: Library space as intrinsic facilitator of the reading experience. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46(2), 102104.

Use this link to join – https://kings.zoom.us/j/93660828235?pwd=MmxaNUszSEZEUTFOcWk0Y3RBUTZnZz09

Please feel free to join us for one, two, or all three meetings during this series, as fits with your schedule and interests, and please feel free to reach out with any questions.

Save the Dates for Fall 2022 Series Meetings:

Thursday, October 20th, 2:00-3:00

Thursday, November 17th, 2:00-3:00

Thursday, December 15th, 2:00-3:00

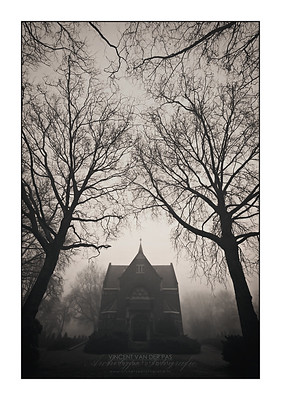

Information Literacy and the Paranormal

It’s that time of year again! The time of year where I can shamelessly indulge in my TV guilty pleasures – the Travel Channel’s slate of paranormal shows. From ghosts to cryptids, to demonic possessions, it’s all there. The part that I love the most, not surprisingly, is the research that happens during the shows. The investigators may interview local historians or library staff, who have historical documents or local history texts conveniently at hand to give them a quick recap of the history of a supposedly haunted space. Some shows may have the investigators actually visit the library or local historical society, and if you’re lucky a microfilm might make an appearance. Other times, it may be the historical society, museum, or library that is itself haunted, which adds a nice twist to the formula.

Some investigators may be more seasoned researchers, and do their own search through digitized newspaper repositories, census records, or other online materials. They don’t mention libraries or archives in these scenes, but we librarians know that they are there, hiding in the background like some information providing specter.

Instead of taking rumor and folklore at face value, these investigators look to find some sort of basis or truth behind the experiences people have. Though some shows achieve this better than others, it is nice to see this attempt at verification demonstrated in popular culture. Hopefully these shows are peaking viewers’ interest in historical research, so they may be interested in learning more about their own town or family, even if paranormal activity isn’t involved.

The one piece of fiction that persists though, even with these “reality” TV shows, is the ease with which the investigators find their information. There is always a convenient edit to condense the time, or a historian at the ready with a prepared pile of documents. Research can be a tedious and messy process, and though it isn’t very “camera ready” it is an important lesson to learn. The right answer isn’t always the easiest one to come by – whether that’s discovering who haunts a building or finding a research article for a class assignment.

Alas, this is a trope that seems to be as persistent as a librarian with her hair in a bun, and her glasses on a chain. (The cardigan gets a pass though; layers are a necessity in libraries with our persistent HVAC issues!) If you want to get even more in the Halloween spirit, Book Riot did a short article earlier this year, highlighting horror movies that feature research at the library Ghosts and murderous clowns, I can suspend my disbelief on their existence, an easy-to-use Microfilm reader? What a bunch of bunk!

Cleaning Up Zoom Transcriptions for Qualitative Research

While sometimes I lament the Current State of Things in academic libraries, I am very glad to be doing qualitative research at this point in time when voice recognition technology has allowed us to create transcriptions of an interview out of the auto-generated captions. Zoom has not only allowed my research team and our subjects, scattered throughout Western Pennsylvania, to come together and share our experiences and attitudes about journal venue choices, but it has also allowed us to collect and analyze our data in an affordable way.

A previous research project I worked on made use of a professional transcription service. For this project, we chose to use our funding entirely for subject compensation. This meant we would be doing the transcription ourselves. While Zoom’s auto-transcription feature is incredibly useful, it still requires some human intervention, especially when faced with less-than-optimal audio quality, non-American accents, verbal tics, or academic jargon. And while in future iterations of this research, we’ll probably request funding for a transcription service, I think Zoom’s auto-transcription is an incredibly helpful tool when that’s not an option.

To help other new library researchers, I’d like to share my workflow for anyone else interested in working with Zoom-generated transcriptions.

Collecting the data:

After receiving verbal consent in the interview, I record to the cloud. While at Pitt, our videos are stored securely on Panopto, but the videos and captions/transcripts are also retrievable from Zoom’s website for up to 120 days.

The Zoom transcript is divided up by timestamps every ten seconds or so.

2:29 SUBJECT: Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur

2:32 INTERVIEWER: adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

2:36 SUBJECT: Ut enim ad minim veniam,

2:41 SUBJECT: quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris

2:43 SUBJECT: nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in

Initial cleaning up the data:

First, I de-identify the transcripts by replacing all instances of the subject’s name with a codename, and then skim through the transcript for any mentions of the subject’s name and replace with [redacted]. Then, I condense all the consecutive lines from the same speaker into one “entry” for readability’s sake, and perform a “find and replace” for what I’ve found are common capitalization errors (lowercase I contractions, for example). This makes the “listening through” round easier so I’m focusing more on the words and less on the format.

2:29 [CODE]: Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur

2:32 INTERVIEWER: adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

2:36 [CODE]: Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in

Listening through:

This is where the bulk of the work is, and so the three of us on my team divide the work after agreeing on a style guide.

As I said earlier, Zoom is fairly good, but doesn’t always get everything right. This round is also where I start adding [tags] for laughter or significant gestures that contribute to the meaning of their words (such as pointing to something in the background or throwing their hands up in resignation). I’ll also italicize any strongly emphasized words if it changes the meaning of the sentence.

But mostly, I just listen and make changes to inaccurate transcriptions as I read along. There are some amusing instances of Zoom “mishearing” things, one example: “The guy was no buffoon” was transcribed as “The guy was notebook phone.” …Indeed! If there are some phrases where I have to listen more than twice to get a sense for what they’re saying, I highlight it and move on.

If the transcription is fairly accurate, I’ll also use this round to start throwing in some basic commas and periods to break up the run-on sentences of human speech. Every few minutes or so, I pause to look back on what I just covered to ensure that the paragraph is making sense. I may also use that time to remove some of the subject’s verbal tics to make sure the ideas aren’t getting lost.

My method of listening through is pretty iterative, so I do it a few times, focusing on different things each time, such as tough sections that I just couldn’t parse. At this point, I might pull in one of my team to get their input. We try to get multiple ears on the transcriptions anyway for this exact reason.

Reading through:

After the listen throughs there are the read throughs where I focus on punctuation and readability. While these readthroughs don’t necessarily need the listening part, it helps to ensure you’re capturing the cadence and meaning of what they actually said. This is also where I check formatting, since this data will be deposited in our institutional repository and it needs to be usable by others.

And that’s how far we’ve gotten so far in this research project! I have only ever done interview research over Zoom, but I would love to hear from librarians and researchers who had to do manual transcription (quelle horreur!) and invite you to share your experiences in the comments.

Connect & Communicate: “Using R Statistical Software for Library Assessment: Do More with Your Data, for Free!” Recording Now Available

The session recording for the September Connect & Communicate Series presentation on using R statistical software for statistical analysis and creating visualizations is now available on the C&CS YouTube channel. Thanks to Sara Kern of Juniata College for an informative and practical session.

Please take a minute to fill out the evaluation form. Your feedback is very important to us, as we are required to submit evaluation data as part of our LSTA grant application.

Learning to Be Together Again

Many of us who work in academic libraries are busy teaching library instruction sessions again. This is my second academic year as a First-Year Experience Librarian, and already I have noticed such a big change from last year. Like many other universities, we returned to full-time, in-person instruction in Fall 2021. Last fall, I noticed a lot of awkward silence during instruction sessions. Most of the activities I did with students utilized tools such as Padlet and Mentimeter, which prevented them from having to speak out loud at all to deliver answers to the activities. However, sometimes I would ask a follow-up question, and I got crickets. I was lucky if I got one person to volunteer a verbal answer, and many times that was with some extra encouragement. Also, it seemed any exercises I did involving groups or partners required more work on my part to get the students into groups. It was obvious to me that, just like everyone else, our students were learning how to be around other people again.

A year later, and I have noticed a big change in this year’s first-year students compared to last year’s. When I ask students to partner up, I usually only have one or two shy students, who I have to help find a partner. Last year I was having to help pair up each student. This year I slightly dialed back on how much I use other tools for students to answer questions. While I still use those tools for many activities, I now have more open conversations built into my lessons as well. This was a bit of a gamble because I didn’t know if the students would be ready for this. However, so far, I’ve been getting at least a few hands up every time I verbally ask a question. There’s also more chatter amongst the students as they file into the classroom, and I have to do much more wrangling when they’re working in groups than I did last year. Students last year were quieter when working in their groups, and when they finished an activity, they would often just scroll through their phones. This year, students turn and talk to one another and joke around to the point where I have to direct them back to the task at hand. I actually taught a class last week where the students were so comfortable and animated around each other that I was struggling to explain the directions for the activities over their talking.

While these instances can be a little frustrating in the moment, I have been happy to see our students acting like normal college students once again. Our sessions are so much fun when the students are engaged and really interacting with the lesson. It’s been refreshing to watch them become friends with one another and begin building that sense of belonging that turns college into their home away from home. I’ve also seen a dramatic increase in students popping by my office to ask a quick question once I’ve taught one of their classes, or coming up to me when a session is complete to get additional help from me. I hope this means our students are finally starting to recover from the pandemic and find solace in human connections once again. Such a big part of college is the friendships we build that last a life time, and it’s been nice to see our students forming those friendships once again.